Today, after one of the most dramatic makeovers in architectural history, and setting plans for mini-Louvres in northern France and the Middle East, the Louvre has established itself as the "must" brand for art lovers and a beacon for France's multibillion-dollar tourism industry.

Last year, the Louvre attracted nearly 9.2 million visitors, more than triple that of 1984 and almost double that of 1989. It is by far the most-visited art museum in the world. Its closest competitor is the British Museum in London, for which there were around 6.7 million entries. A decade from now, according to the Louvre, annual visitor numbers could be on the brink of 12 million.

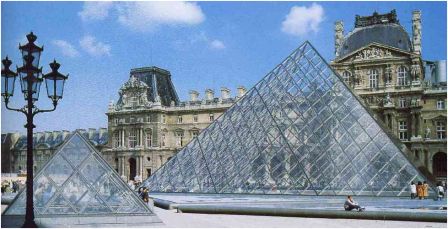

The springboard to all this was the transformation of the Louvre in 1989 by then French President Francois Mitterrand, who chose a massively controversial design for a new underground entrance.

The design, by Chinese-born American architect I. M. Pei, was blasted by many as kitschy and out of place, and part of a "pharaonic" reflex by Mitterrand to set his mark on Paris. Mitterrand viewed the pyramid and a massive archway, in the defence business district, as bookends of a vast axis emblazoned by the Champs-Elysees with the Arc de Triomphe in between.

To the consternation of critics, the pyramid became an instant hit.

"The Pyramid has become a symbol of Paris, in fact the Louvre is probably the only museum in the world where people come to see the entrance," says Louvre director Jean-Luc Martinez.

Compared with the old days, when its lofty halls and marble floors echoed to the footsteps of French intellectuals and bourgeois families, 70 per cent of visitors today are from abroad.

Many of them are groups who are whisked through on a "Highlights" tour - Mona Lisa, the Venus de Milo, Egyptian mummies, a Michelangelo and a few Impressionists - before being rushed to the Eiffel Tower, Notre Dame or trip on the River Seine.

Paris' stuffier art lovers carefully choose the month, and the hour, they wish to visit the Louvre. At peak time, the Mona Lisa - "La Joconde" - has to be glimpsed behind a wall of people five or six deep, many of them taking selfies with the iconic picture in the background. The painting itself lies behind a thick glass screen to protect it from camera flash, and several security guards stand by.

Even getting into the museum can be a feat in itself. On most days, queues begin forming at least half an hour before the museum opens. At almost any time of day, long lines of people wait at ticket counters, the information desk and security checks. The atrium, designed by Pei to be lean and light and airy, can reach levels of industrial noise and tropical heat simply because of the sheer numbers of humans.

Back in 2006, Pei warned a fix was needed. "The problem is not the pyramid itself, but what's under it. There is now a security tent for checking bags, and there are huge queues of people waiting for tickets," Pei told Architects' Journal. "The pyramid is not functioning as expected ... There is not enough public space - it's a scale problem."

Martinez is now pushing through a €53.5 million ($84.5 million) refit. The ticket booths will move, the Pyramid entrance doors will be expanded and the signs inside the museum - all 38,000 of them - will be translated into three languages, including English, to help the hundreds of people each day who get lost.

"There's a real problem with numbers," said art historian Didier Rykner, a prominent critic of the Louvre's strategy. "There are too many people, and the result is that they are spending lots of money adapting the museum to try to cope with it." Appointed last year, Martinez is seen by some as signalling a "back-to-basics" approach after 12 heady years of expansion.

Under his predecessor, Henri Loyrette, the Louvre focused increasingly on media-friendly special exhibitions as opposed to showcasing its permanent collections, opened a new museum in Lens in the northern French rustbelt and agreed to lend its name - and some of its collection - to a museum in Abu Dhabi due to open next year.

The projects have triggered criticism of brand "stretch" and ingratiation with oil money.

More than 4600 art historians and conservationists signed a petition lashing the Louvre Abu Dhabi deal - a 30-year agreement in exchange for US$1.3 billion ($1.6 billion) -- as likely to gut French museums of national treasures, including works that are too fragile to be transported safely.

"I think that [the] Abu Dhabi [deal] was a huge mistake," Rykner told the Herald. "I don't have the complete list, but I do know that there are some major works on it which should never have been rented out - it's a total scandal."

Alain Quemin, a professor of the sociology of art at Paris VIII University, said France's tightening state budgets meant the Louvre "has no choice" but to continue to pull in the crowds and coax money from foreign tie-ups.

Money from the Abu Dhabi contract, not state subsidies, will fund the latest alterations.

"The purists may not like this but there's another perspective, which is that those who go to the Louvre on a lightning tour and enjoy it are quite probably people who would not have set foot in the museum if the visit was culturally more demanding," Quemin told the Herald.