Let Them Eat Brioche

Alison Gofton Article

Tarbes, our closest city, does not rate in the tourist guides of France, something that needs to change. The adage “never judge a book by its cover” surely applies to Tarbes, especially when it comes to food.

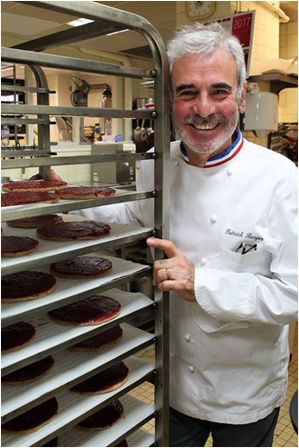

Tucked off the shopping boulevards lie many unexpected culinary discoveries, a treasure trove of talent and taste in this often unfairly media-neglected city. On an unremarkable corner, behind glass windows showcasing towering displays of candy coloured macarons, is Patrick Berger MOF (Meilleur Ouvrier de France), master patissier, traiteur and owner of Royalty, a chic Salon de The.

Each day Patrick (pictured above) and his staff hand-craft exquisite pastries and desserts, and a comprehensive selection of artfully decorated dishes to be served in-house for lunch, or boxed for “emporter” — take-away — for a traiteur is a food boutique specialising in beautifully presented dishes to take home; food to be savoured not scoffed.

Patrick, like so many artisans here, learned his trade as a youngster, working at the pastry bench beside his dad, whose business Royalty once was. I’m a regular here, attempting to taste my way through the jewel-like patisseries, but I fear both my time will run out and my hips will give out!

Behind front of house, Patrick is giving me a lesson on creating the perfect brioche. Proudly, Patrick extols the virtues of each ingredient; for him, each one must be of the highest quality and each one’s provenance is paramount. It’s this passion for each individual ingredient that, for me, differentiates the French people’s love of food from ours.

Flour, milled from wheat grown in the Pyrenees, and eggs (all size 55 grams for consistency) are sourced from a local farmer. Butter must be unsalted — called doux here — and is the only product sourced outside the region. Although Patrick would like to use hand churned butter from the Pyrenees, he says it’s difficult as the make-up of artisan-produced butter varies with the seasons and he needs consistency of structure; his butter comes from Normandy bearing an AOP.

With these ingredients at hand, we begin to make a firm dough from flour, salt, yeast sponged in milk, and eggs —lots of them. This heavy, solid dough is kneaded well to work the gluten, then, gradually the butter, at room temperature, is added slice by thin slice until a very soft, dough forms.

It takes ages, more time than I would have thought. To my surprise, the dough is not left to rise but refrigerated overnight so it can become firm, like a chilled sweet pastry dough. Brioche, Patrick tells me, cannot be rushed. Early next morning, the cooks take the firm, cold dough, cut, weigh and shape it into classic top-knot buns or roll and fill with spice and sugar or glacé fruit.

Several hours will pass before the brioche has risen sufficiently to be baked. Patrick washes the brioche liberally with egg glaze before cooking the fluffy mounds at a high temperature for a short time. Fresh from the oven, the brioche is simply wonderful. Like Otago cheddar cheese, good things really do take time!

Baby brioche buns with glace fruits

10/4/2017

10/4/2017